Despite the title, the c. 1818 “Devonshire Rules for Making and Managing Cider” aren’t a step-by-step guide to making and managing cider. Instead they’re a user’s manual for a double-screw apple press, with a wealth of orcharding suggestions and cidermaking details. It’s also a revealing look at how cidermaking knowledge was communicated in early America.

The “Devonshire Rules” are in the Benjamin Vaughan papers at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. Vaughan was an English radical politician, whose support of the French Revolution forced him to flee England in 1794. After a few years in France, he settled on land inherited from his mother in Hallowell, Maine. He spent the rest of his life amassing a private library rivaling Harvard’s, pursuing his agricultural, political, and scientific interests, and maintaining a constant correspondence with people on both sides of the Atlantic.

Although the “rules” are in his handwriting, Vaughan didn’t author them. As the title suggests, the rules were originally written in Devonshire, one of England’s famous cider regions. They reflect what some ciderists were doing there and appear to have been written for other professional and serious English cidermakers. Based on a note in the margin of the “rules,” a Captain James Vasey sent them to Vaughan. It’s unknown where Vasey took the rules from, if he copied them in a letter or sent along a publication, or why he sent them.1 Perhaps he was aware of Vaughan’s interest in horticulture, or perhaps Vasey was simply helping round out Vaughan’s ever-growing library.

Vaughan must have thought the rules important enough that he considered publishing them. Details within the manuscript reveal his editorial efforts and suggest his desire to see them in print.

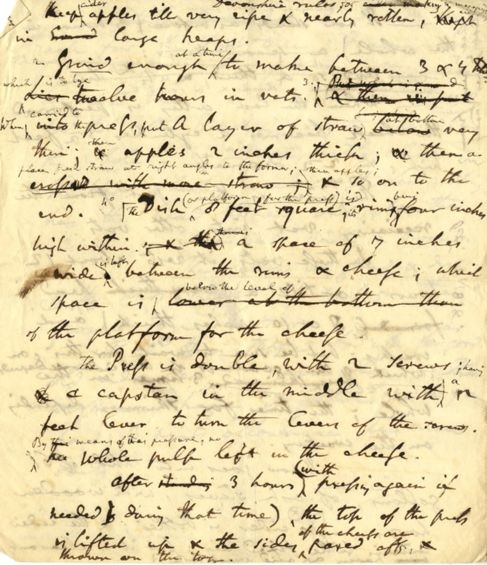

Vaughan transcribed the rules twice. The first version, entitled, ““Devonshire rules for making and managing cider” shows a number of clarifying corrections. This was possibly Vaughan’s attempt to improve on the original author’s descriptions. A second transcription, entitled, “Rules mentioned by a large Devonshire farmer in Devonshire (in England) for making and managing cider & orchards; by a large Farmer in Devonshire, in England” also shows several clarifying notes. Unlike the first version, the second version also includes spelling and grammar edits, suggesting he was proofing it to send to a printer. Two additions in the second version offer further clues to its potential use. The second version’s title is more explanatory, identifying the Devonshire in question as the one in England. It also includes a reference to New Jersey apples not present in the first version. These two edits suggest this was Vaughan’s attempt to rewrite the rules for an American audience.2

Despite Vaughan’s many edits, the content differences between the two versions are minimal. They both describe a very similar milling and pressing process: after sweating the apples, one should grind enough to make three to four hogsheads of 61 gallons each (or 183 or 244 gallons of cider). Once ground, the pomace should be left in the mill for 12 hours (to macerate). After that, the cidermaker should build a cheese with the pomace in a double-screw press. Once built, press the cheese and let it stand for three hours. After that, unscrew everything, rebuild the cheese, and press again for three more hours. This should be done three or four times. After pressing, the juice should rest in a vat for 12 hours, be skimmed three times, and then barreled in a hogshead. After eight or ten days, the cider should be racked into a new barrel, and then racked four or five more times every two weeks or until the cider is clear.

Along with milling and pressing, the rules also touch on orcharding. They advise that every three to four years the turf around the trees should be removed and a layer of manure three to four inches thick spread around. To help keep everything healthy and growing, the rules also note that cows and horses are allowed in the orchard, but sheep are not (they tend to destroy the trees). No mention is made of pigs.

Tucked in throughout the instructions are a wealth of important cidermaking details. The rules note that the hogshead of cider should be elevated on a barrel horse and the cider should be racked from that barrel into a new one via a cock (spigot). They also suggest that the cider should be barreled and cellared for five years before being tapped, but it could be served to workmen at two years.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

The rules note that some apple trees are grafted, but the majority are “natural,” or seedling. In the second version, that line is crossed out, suggesting that it is either unnecessary to mention it because that’s the American reality already or doesn’t suit the American situation (though it is likely the former). Both versions remind the reader that sour and sweet apples are mixed to make cider and that the finished cider has little carbonation and “an acid-sweet taste.”

Unique (so far) to the “Devonshire Rules” are the time estimates for several steps, including hours for:

Resting ground apples in vat 12

Pressing (4 times at 3 hours per) 12

Resting juice in vat 12

TOTAL 36

That’s 36 hours to make 183 to 244 gallons of cider. The “rules” don’t include time estimates for several necessary tasks, including moving the apples from where they were left to sweat to the mill, milling the apples, transferring the pomace to the press, building and rebuilding the cheese on the press, filling barrels from the vats, cleaning vats and three or four hogsheads before they are used, and the multiple rackings each barrel was to go through. Along with the financial investment for equipment, the Devonshire rules suggest a steep time investment as well. It is possible that American cidermakers, often making for their own use and for local trade, reduced the number of steps, the time invested, or a bit of both. Wealthier makers, who may have been more inclined to follow the steps laid out by “rules,” were able to do so because they used hired or enslaved labor.

Though it answers a number of questions about early cidermaking, it also leaves us with new ones. How many bushels or pounds of apples was enough to make three to four hogsheads of cider? Did anyone in America really rack cider 5 times or cellar cider untouched for five years? And why didn’t Vaughan publish them? Did another project capture his attention or did someone tell him American cidermakers would never do all of that?3

You can see Vaughan’s original transcriptions of the “Devonshire Rules” in the collection of the APS here.

You can find my transcription of Vaughan’s “Rules” here.

You can visit the Vaughan Woods and Historic Homestead, Benjamin’s estate, in Maine.

************************

1. Both Vasey and the source of the “rules” remain unidentified.

2. Perhaps he intended to publish them in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Vaughan was admitted as a member of the Society in 1786 and his brother, John, had been librarian there since 1803.

3. Also, did Americans ever use the cylinder of cheese from the press as a backlog in their fires, as the “rules” suggested?