English cider helped ferment the American Revolution. Not drinking it, taxing it.

In 1763, at the end of the French and Indian War, Great Britain stood victorious and debt-ridden. Americans today often think that Parliament immediately taxed the colonies to pay down this debt, which had doubled during the war to £132.6 million.1 But before they taxed Americans, Parliament taxed fellow Englishman first. Just as the war was drawing to a close, Parliament voted on a new tax entitled “An Act for Granting to his Majesty Several Additional Duties Upon Wines Imported into This Kingdom, and Certain Duties Upon All Cyder and Perry,” which was intended to raise £3.5 million. For obvious reasons, the name was often shortened to the Cyder Act.2

Today, if the Cyder Act is mentioned at all, it is often told as the charming tale of how appealing cider was and how poorly Parliament acted. However, it was more than an unpopular tax on a popular drink. In fact the Cyder Act was seen as an invasive tax that gave unlimited power to excise collectors, created unprecedented government oversight into private life, and was a burdensome tax on poor people. Over the three years the act was in place, it stirred resentment in England and taught American colonists how to protest effectively.

Parliamentary debates over the act began in late 1762. By March 1763 the act was drafted and approved. One of the first public announcements was in the March 1763 edition of the London Magazine. Laid out in 73 sections, the Cyder Act established new duties on imported French wine and vinegar and imported cider, created three lotteries, and implemented heavy taxes on cider and perry production and transportation (but not sales).

The cider and perry portion of the Cyder Act required that after 5 July 1763, all cidermakers, no matter if they made strong or weak cider for personal use or commercial sale, pay a 4 shilling per hogshead tax. Before they could even begin milling their apples, cidermakers were to apply to the local excise office in writing for permission to make cider ten days before they began, and include the place where the cider was to be made, all equipment used (and whether it was theirs or another’s), and the location where the cider would be stored. Once approved, they could begin to make cider. Makers had to specify what equipment would be used, but if they were going to borrow or rent another’s mill and press, the equipment’s owner also had to submit a written statement authorizing that use. To prevent fraud after that start date, makers had to submit an inventory of cider on hand before 5 July 1763, which would be exempt from the tax. Families who did not make for sale but for their own use, were still charged 5 shillings per person in the household over eight years old per year. If a family did decide to sell, they needed to apply for a one-time license. To ensure that there was no funny business, the act also prohibited the transportation of six or more gallons without written consent. Excise officers were granted the power to inspect any home, cellar, or outbuilding without notice to make sure each household and maker was in compliance with these rules.

Cider, it seemed to many, was how the British government would abridge British rights. Protests bubbled up even before the act passed. One member of parliament reminded the house that “every man’s house was his castle… If this tax is endured, it will necessarily lead to introducing the laws of excise into the domestic concerns of every private family, and to every species of the produce of land.” Almost immediately upon its release, others protested the act saying the “excise strikes at the constitution and are grievous and oppressive.” The Cyder Act seemed to empower excise collectors to be both judge and jury in all cases, robbing people of their right to trial by jury. Other arguments noted that the act permitted excise men to to search private property without restraint or cause, including those of the peers, and that it hurt poorer farm families who made cider and perry for their own use.3

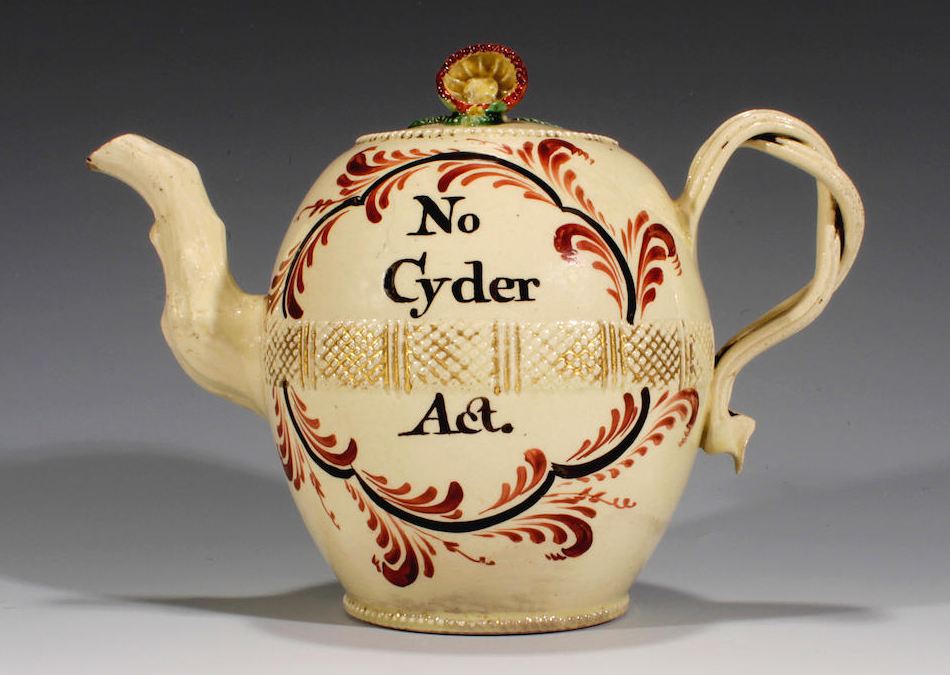

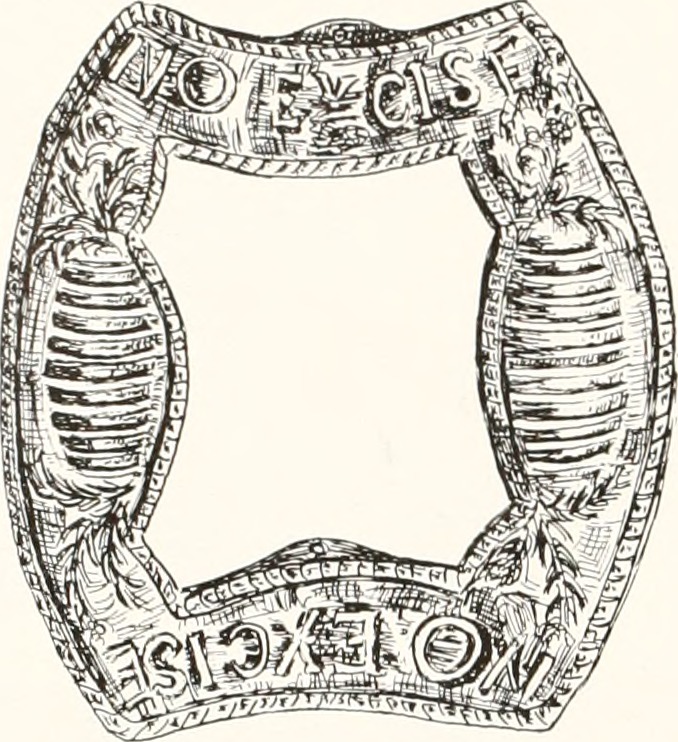

Protestors created anti-excise pamphlets, prints, and products. Reaching back thirty years to the protests of the 1733 Excise Tax, which also allowed almost unrestricted searches and seizures, the Cyder Act protesters resurrected the slogan “Liberty, Property, and No Excise,” putting it and variations of it on all kinds of goods.4

Throughout the rest of 1763 and 1764 attempts were made to change the law so that it was less onerous to the working poor. It took until 1765 for the act to be amended. The changes included extending the time to pay all fees from six weeks to six months, reducing the fees for personal use from 5 shillings to 2 shilling per person eight and above in the household per year, giving makers ten days to submit a form for borrowing equipment, and cider equipment owners no longer had to apply for permission to lend their equipment to others. The new act also reduced fees for hindering excise officers in their duty, and penalized officers for not submitting correct reports.

The hope was that this would be enough to calm the roiling opposition in England.

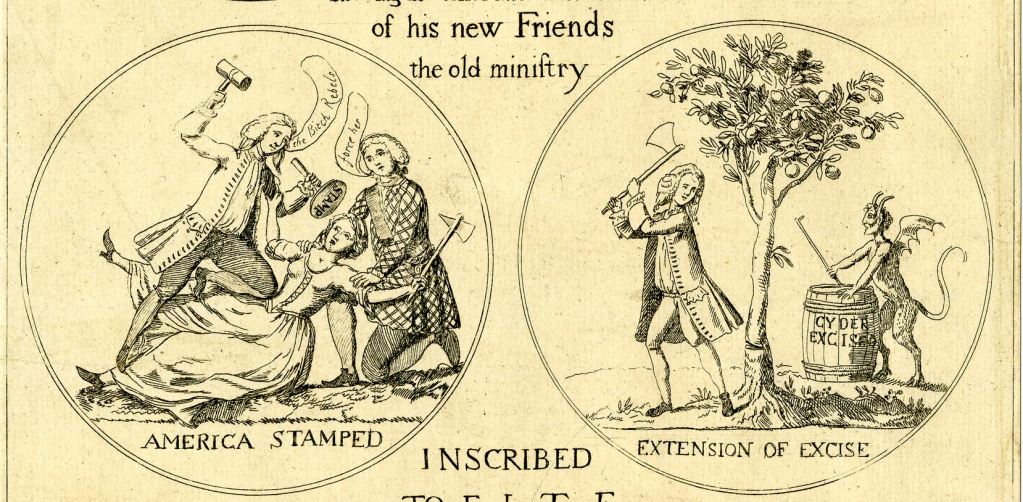

Americans remained untouched by the Cyder Act, but American observers were deeply interested in it. Newspapers throughout the colonies reprinted articles from British newspapers about the protests throughout England. At first, these seemed like distant events, but in 1765, as the Stamp Act was adopted, Americans suddenly felt the intrusive power of Parliament.5

Fresh in their minds, the Cyder Act protests became a model for some of the American response to the Stamp Act. As English protestors of the Cyder Act viewed the excise, Americans saw the Stamp Act as being unnecessarily invasive and costly. Taking some inspiration from the Cyder Act protests, Americans adopted the slogan, “Liberty, Property, and No Excise.”6 A similar range of “No Cyder Act” products was created for America, now featuring the “No Stamp Act” slogan.

American protest efforts succeeded relatively quickly. The Stamp Act, approved in 1765, was repealed in March 1766 before it ever took effect. However, it took three years for the Cyder Act protesters to successfully win repeal. In April 1766 the Cyder Act was replaced by a new tax on cider wholesalers and retailers.

The Cyder Act was supposed to settle the British Empire. Instead it sprouted protests in England and planted the seeds of rebellion in America. If the Cyder Act had succeeded, it is possible Parliament would not have turned to the Stamp Act and Americans would not have had such a recent example to follow. In other words, without English cider, there might not have been an American Revolution.

************************

1 Jeremy Land, “The Price of Empire: Britain’s Military Costs During the Seven Years’ War” (masters thesis, Applachian State University, 2010), 36, https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/f/Land,%20Jeremy_2010_Thesis.pdf..

2 Spelling in the eighteenth century was not standardized. Cider could be spelled a variety of ways, including with a “y” instead of an “i.” For more on this, see “Cider By Any Other Letters Spells as Sweet.”

3 For “castle” quote see, The Parliamentary History of England, From the Earliest Period to the Year 1803,v. XV A.D. 1753-1765 (London: T.C. Hansard, 1813), 1307; For “grievous and oppressive” quote, see John Wilkes, The North Briton, no. 43 (Dublin: J. Potts, 1763), 148; For other protests see, R. Baldwin, The London Magazine, or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer (May 1763): 255-258 and R. Baldwin, The London Magazine, or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer (June 1763): 287-290.

4 For 1733 use of “Liberty, Property, and No Excise” see Stephen Duck, Poems on Several Subjects, 7th ed. (London: J. Roberts, 1730), 30; John Winstanley, Poems Written Occasionally by the Late John Winstanley (Dublin: S. Powell, 1751), 192; An Enquiry Into Some Things That Concern Scotland (Edinburgh: 1734), 47; William Belsham, History of Great Britain, From the Revolution to the Session of Parliament Ending A.D. 1793, vol. I (London: G.G. and J. Robinson, 1798), 245; A Collection of Parliamentary Debates in England, From the Year 1668 to the Present Time, vol. XI (London: John Torbuck, 1741), 347.

5 For news of the Cyder Act published in America, see New-York Mercury (no. 646), March 12, 1764, 3; The Massachusetts Gazette (Supplement), November 14, 1765, 1; Pennsylvania Journal, or, Weekly Advertiser (no. 1202), December 19, 1765, 2; The Boston Evening-Post (no. 1602), May 26, 1766, 2.

6 For example, a Stamp Act protestor in Boston published a broadside entitled, Liberty, Property and No Excise: A Poem Compos’d On Occasion of the Sight seen on the Great Trees, (so called) in Boston, New-England, on the 14th of August, 1765.