In 1881 the “Alphabet of Intemperance” said

C is for Customs, which bind us in chains,

Destroying our reason, debasing our brains,

From which all should break without waiting a day –

There’s danger in waiting, there’s death in delay.1

Although this “C” was not for cider, it was certainly about it.

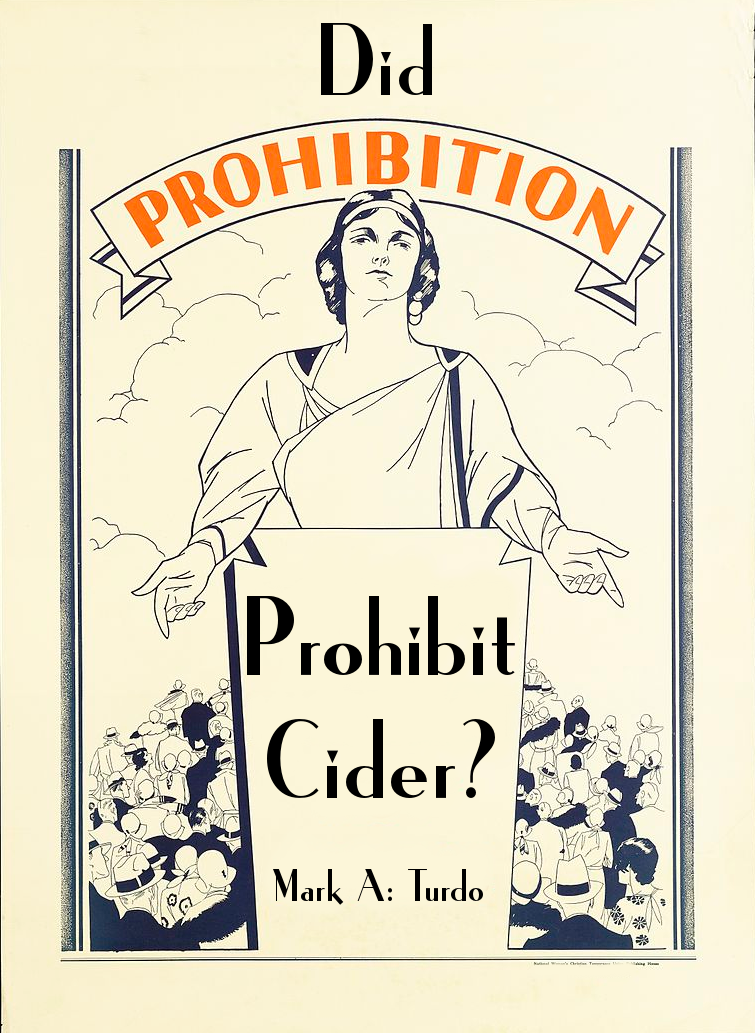

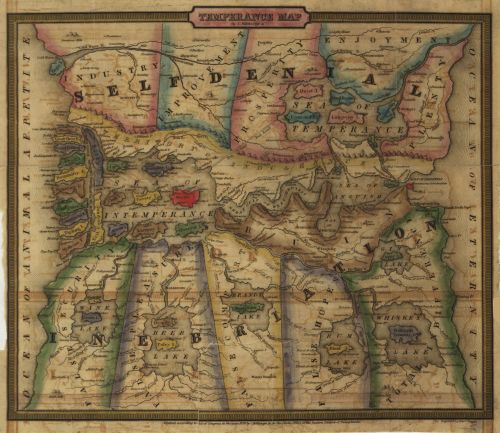

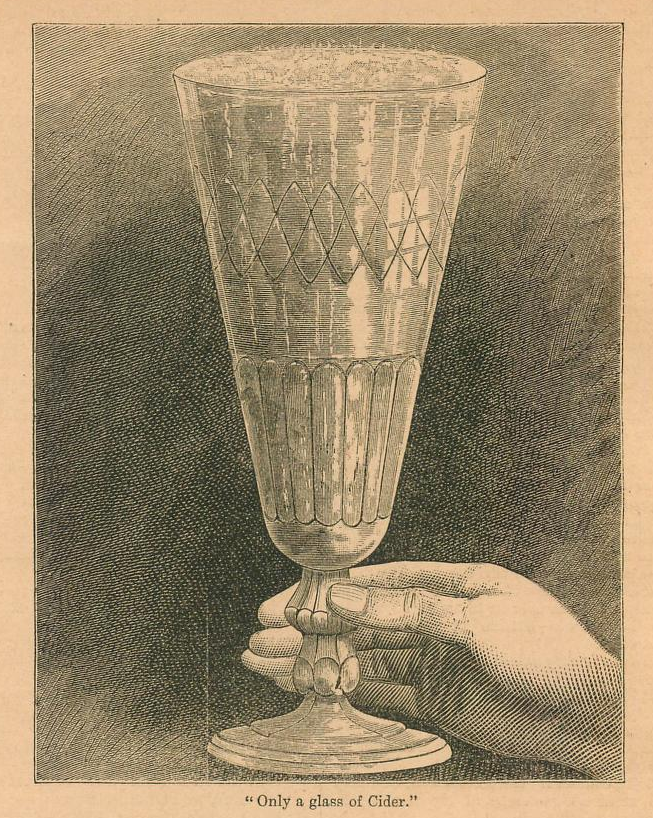

By the 1880s, cider had been a part of American culture for centuries. Its long presence in American life meant many, including some Temperance followers, never saw it as a temptation, much less a danger. Why, they wondered, would Temperance ban something that had always been there and was, anyway, mostly harmless? Shouldn’t cider get a pass?

This debate over whether cider should be an exception (or a loophole) was called the “cider question.” It began shortly after Temperance targeted cider in the 1830s and continued through Prohibition in the early twentieth century. While the “cider question” was intended to moderate Temperance’s reactions, it had the reverse effect, and made Temperance leaders more severe. For the rest of the 1800s and into the early 1900s, leaders answered the “cider question” by saying that cider in every form, alcoholic and sweet, should be banned.

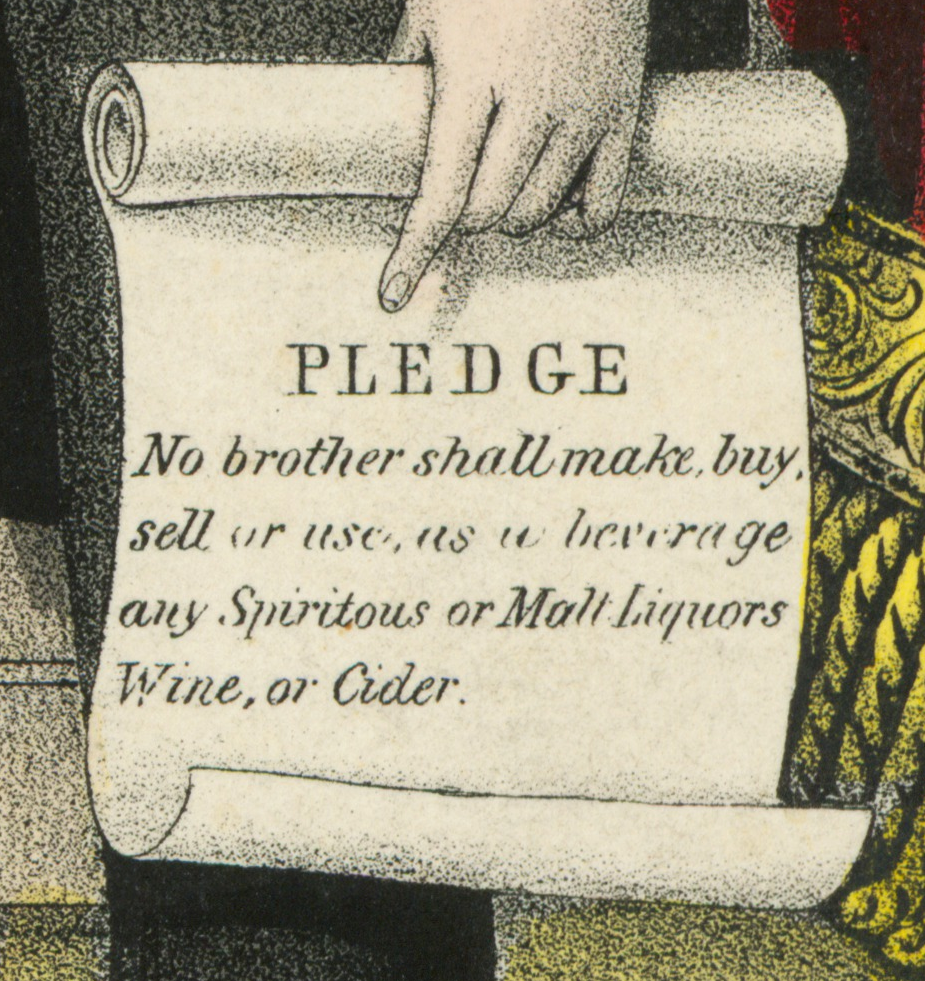

Temperance leaders did not always consider cider a problem. As Temperance writer James Black put it in 1869, “In the infancy of the Temperance reform, say from 1826 to 1832, a pledge, including spiritous or distilled liquors, was the only pledge in force, so that a man could be an active member of a temperance society and yet use and dispense in his household, wine, beer, or cider.” When Temperance began targeting cider, many members, who had grown up with it as part of their daily life, were at a loss to understand why and began asking the “cider question.” Black noted that “this cider question has at various times created great trouble in all temperance organizations…”2

From the leadership’s perspective, part of the trouble was that some members held, “the erroneous idea that [wine, beer, cider and malted drinks] are harmless if not beneficial.”3 In 1840, just a few years after Temperance turned against cider, one member objected to the expanded list of prohibited drinks, claiming, “that wine, beer, and cider are not distilled spirits, and should therefore escape denunciation.”4 Another Temperance writer observed that “Many persons have no idea that cider and perry are inebriating.”5 This last one was either a dubious statement or that was weak cider. In 1881 the rhetorical question was asked and rather condescendingly answered: “Shall cider come under the ban of the pledge? That it must, is almost too evident to admit of discussion…”6 As late as 1915, one writer noted that cider was thought to be “harmless and necessary” in many places.7 And five years later, as Prohibition was about to take effect, it was noted that “some people seem to still wonder why cider is included in the list of intoxicating liquors.”8

As these observations demonstrate, Temperance leaders grew exasperated with the “cider question.” When members continued to ask it, leadership doubled down, saying that not only was alcoholic cider a problem, so was sweet cider. Although some of the more moderate (and accurate) among them observed that, “cider is not intoxicating before it ferments,” more strident leaders said that, “Sweet cider is the bone of contention. Do not all our members know that cider in any form or shape, as a beverage, is a violation of our pledge? Never could a question be plainer than is this.”9

Temperance writers began using a “slippery-slope” argument. One writer noted that “the friends of total abstinence must discard the use of cider as a beverage, whether sweet or sour. True, there is no intoxicating element in unfermented cider; but then fermentation begins much sooner than people suppose.” He explained that “it is impossible for drinkers to tell when new cider becomes intoxicating…” and so it’s safest to simply avoid it altogether. The writer went further, saying, “If you have any regard for us, for Heaven’s sake don’t set the example of drinking even sweet cider.”10

In 1859, the Independent Order of Good Templars tried to make Temperance’s anti-sweet cider stance clear. They laid out seven violations of the Temperance pledge incurred by drinking sweet cider. These included:

1. Drinking of sweet cider is a violation of the Good Templar’s pledge.

2. The use of expressed juice of the apple as a beverage is a violation of our pledge.

3. It is a violation of the spirit and intent of the obligation of the Order of Good Templars to imbibe unfermented wine or cider.

4. In the opinion of this Grand Lodge, the juice of the grape is wine, and the juice of the apple is cider, whether in a fermented or unfermented state, and consequently the use of either as a beverage is a violation of the pledge.

5. To drink cider in any state as an article of food is decidedly a violation of the pledge, for in such cases it becomes a beverage.

6. Drinking the juice of the grape or apple, in any state as a beverage, is a violation of our obligation.

7. The use of currant wine or expressed juice of the apple, as a beverage, is a violation of the pledge.11

Although they attempted clarity with this list, all they achieved was redundancy. These seven violations could have stopped at #1 and it would say the same thing as all seven.12

Though they went to extreme lengths to answer it, Temperance leaders were always stumped by the “cider question,” focusing on the slippery-slope arguments of drinking cider in any form. Cider supporters, on the other hand, focused on the feelings of health, home, and history it engendered. Missouri Senator George Graham Vest summed up this view on the floor of Congress in his arguments on June 16, 1897. Arguing against including cider in the Dingley Tariff bill, Vest said he did not, “…propose to open up the temperance question, but I am defending cider, the liquid of our boyhood, the beverage that “cheers but not inebriates,” that sparkles at every New England festival and in every New England home and in the West and South wherever the apple is raised and used.” And that, “If whiskey could have an advocate, how many advocates ought cider to have, the beverage of sobriety, the beverage of home?”13

Though they agreed on little else, both Temperance leaders and cider supporters agreed on one thing: the “cider question” was not always about cider’s present, but America’s past. For cider supporters the answer was because it was always here, it always should be. For Temperance leaders it was a false-friend, familiar but dangerous.

No matter how one answered it, the “cider question” demonstrated that though cider was no longer the common American drink, it had become the customary drink of America.

*************************

1. Ebenezer Bowman, “Alphabet of Intemperance, No. 171” in Temperance Tracts Issued by the National Temperance Society (New York: National Temperance Society and Publication House, 1881), 1; https://books.google.com/books?id=wkQ2AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=%22cider%20question%22&pg=RA106-PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

2. James Black, “The Cider Question” in The Cider Question and Its Relations to the Temperance Cause, (Boston: J.M. Usher, 1869), 3; https://archive.org/details/ciderquestionits00unse/mode/1up.

3. “The Cider Question,” 3.

4. “What Shall Be the Drink of Reformed Men?” in Permanent Temperance Documents (1840), 262; https://books.google.com/books?id=DNsXAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA1-PA262#v=onepage&q&f=false.

5. “English Cider” in The Cider Question, 10.

6. William M. Thayer, “Cider in the Pledge, No. 66” in Permanent Temperance Documents Annual Report of the American Temperance Society (1881), 1; https://books.google.com/books?id=wkQ2AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=%22cider%20question%22&pg=RA35-PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false .

7. Francis A. Lane, “Brewing Interested and Activities,” The Temperance Cause XXXVII, no. 4 (April 1915), 31; https://books.google.com/books?id=-9OPJDlUL3kC&dq=temperance%20cider&pg=RA1-PA31#v=onepage&q&f=false.

8. “The Cider Question,” The Temperance Cause XLII, no. 4 (April 1920), 25; https://books.google.com/books?id=-9OPJDlUL3kC&dq=temperance%20cider&pg=RA8-PA27-IA10#v=onepage&q&f=false.

9. “Cider in the Pledge,” in Cider Question, National Temperance Society (1881), 12. Cider Question, 1863, 2.

10. William A. Thayer, “New Cider a Dangerous Beverage, No. 5” in Temperance Tracts Issued by the National Temperance Society (New York: National Temperance Society and Publication House, 1881), 1-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=wkQ2AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=%22cider%20question%22&pg=PA5-IA2#v=onepage&q&f=false.

11. Simeon R. Chase, ed., A Digest of the Laws, Decisions, Rules and Usages of the Independent Order of Good Templars (Pennsylvania, 1859), 41-42; https://books.google.com/books?id=qS9HAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=Drinking%20of%20sweet%20cider%20is%20a%20violation%20of%20the%20Good%20Templar%E2%80%99s%20pledge.&pg=PA42#v=onepage&q&f=false.

12. This reminds me of George Carlin’s summation of the ten commandments.

13. Vest’s argument was that America exported more cider than it imported, and therefore didn’t need protective tariffs. Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates, v. 30, Part 2, (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897), 1750; https://books.google.com/books?id=ViJ36PquBcYC&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=cider%20question%20temperance&pg=PA1750#v=onepage&q&f=false.

![temperance weekly eastern argus, published as eastern argus. (portland, maine) • 07-14-1829 • page [3]](https://pommelcyder.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/temperance-weekly-eastern-argus-published-as-eastern-argus.-portland-maine-•-07-14-1829-•-page-3.png)

![temperance republican star, published as republican star and general advertiser (easton, maryland) • 07-21-1829 • page [3]](https://pommelcyder.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/temperance-republican-star-published-as-republican-star-and-general-advertiser-easton-maryland-•-07-21-1829-•-page-3.png)

![temperance new hampshire sentinel, published as new-hampshire sentinel. (keene, new hampshire) • 03-24-1836 • page [3]](https://pommelcyder.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/temperance-new-hampshire-sentinel-published-as-new-hampshire-sentinel.-keene-new-hampshire-•-03-24-1836-•-page-3.png)

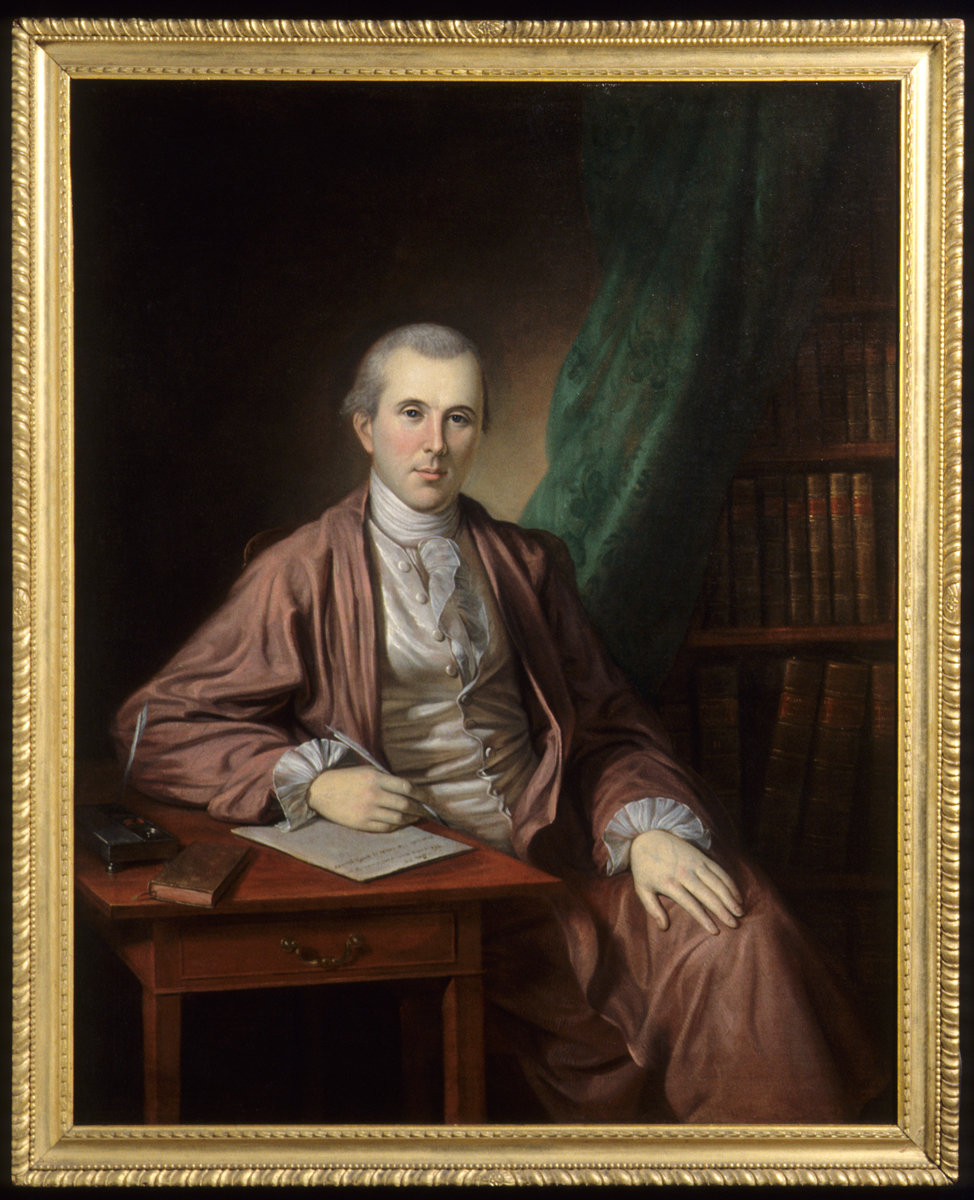

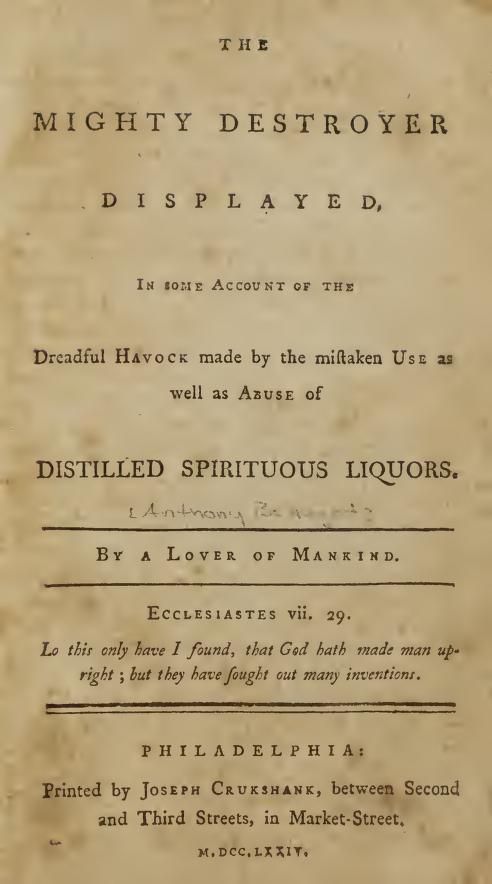

in 1774 Anthony Benezet, a Philadelphia teacher and Quaker, published

in 1774 Anthony Benezet, a Philadelphia teacher and Quaker, published