Author’s Note: Last time I looked into the etymology, or origin, of the word cider. In this post I’ll take at the orthography, or spelling conventions, of cider over time. I have no doubt I missed things.

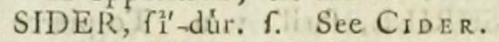

From A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, by Thomas Sheridan, 1789.

In Middle English what we spell as “cider” was spelled like this:

Cedir, cedyr, cider, cidre, cither, sider, sedir, seider, seyder, sider, sidre, sidur, sither, sychere, sydir, sydur, sydyr

This is almost certainly not a complete list. Until the nineteenth century, English spelling was largely phonetic – people spelled how they pronounced things. Their understanding of which letters made what sounds was often local and widely variable. Those possible spellings came from a variety of sources, none of which English grammarians ever consistently streamlined or standardized. Hence all of our “rules” and their various exceptions.

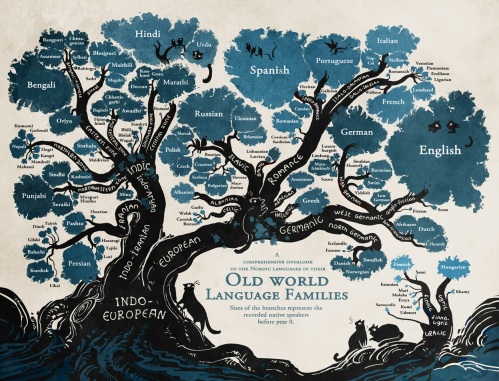

This is because English is a blended language. It’s roots are Germanic with Scandinavian, German, Latin, French, and Greek words, among others, grafted onto it. As the Anglo-Saxons, and later the English, encountered new cultures (and by encountered, we mean were invaded by), they borrowed words their into English.

Not only did English borrow words, they also imported letters to represent new sounds for its ever-evolving vocabulary. In the 7th century Christian missionaries brought the Latin alphabet to England, which replaced the Germanic runic alphabet. With Latin as the base, other letters were added to represent the sounds of these foreign words. Over time this led to orthographic anarchy.

Sometime before the 14th century literate Christian missionaries began establishing spelling guidelines. They tried to honor the original language by retaining something of their original spellings, even if the pronunciations of letters was different from what was accepted English spelling. For example, if it was originally a French word they kept the French spelling and pronunciation. This non-standardized standardization is what left us with so many redundant letter sounds and spellings.

Just after these new “standardized” spellings were being set, English pronunciation went through a change. Known as the Great Vowel Shift (GVS), it changed how people spoke their vowels. However, the spelling standards which had been created before the GVS were not revisited. This is why so many spellings and pronunciations often seem mismatched to modern English speakers.

With that brief background, let’s take a sound-by-sound look at how all of this led to the various cider spellings.

/s/ Sound – C & S

Latin got the S from the Greeks and English later inherited the S with its /s/ sound from Latin.

The letter C also comes from Latin. However in Latin all Cs were pronounced as we would a K sound. After the Fall of Rome, Latin split into what we call the Romance languages, including French. Over time, French slowly shifted the C from a K sound to a soft /s/ sound. So the Latin cisera (ki-sera) became cidre (see-dra). It’s a process called assibilation. The French word for “cider” became sibilant.

In 1066 French-speaking Normans conquered England and brought with them their S-sounding Cs. These Cs worked alongside Ss, already in English to create /s/ sounds.

/ī/ Sound – I & Sometimes Y (and Ey and Ei)

The letter I and the /ī/ sound is also from Latin.

Sometimes Y also makes an /ī/ sound. In the 7th century Irish monks began translating church documents into early English. They adopted the Greek Y to represent sounds which didn’t exist in Latin. Originally this Y was more of a /ü/ sound. During the Great Vowel Shift, this /ü/-sounding Y shifted to more of a long-i sound. After the GVS words that had a long-i sound could be spelled with either an i or y.

From at least the early Middle English period the long-i sound could also be spelled as “ey” or “ei.”

/d/ Sound – D & TH

Our D comes to us from the Latin alphabet. However, words with a D could be pronounced with a D sound and sometimes a TH sound. Think how sometimes we say “that” and sometimes we say “dat.” The two sounds are pronounced very similarly, and in some times and places were heard to be interchangeable.

/ər/ Sound

While the /ər/ sound occurring at the end of some words comes into English from German and French words, it’s the French spelling of that sound that has caused some confusion. In French that sound is spelled -re, but by Middle English it was sometimes spelled -er. Both spellings represented the same sound from just after the Norman Invasion through the 18th century. Today British English still uses the -re spelling in some words, while most American English words use -er.

By Late Middle English -ir, -ur, and -yr all sounded close enough that they could also be used to spell the /ər/ sound.

As we see above, the sounds of various letters came into English from a variety of sources. Since there was no standardized way to spell words, only various options to spell various sounds, it is easy to see why the word cider came in as many styles as the drink.

For anyone researching pre-nineteenth-century cider, knowing about these spellings is important as more and more historical resources are digitized and online. One can’t just type in “cider” and expect to find everything.

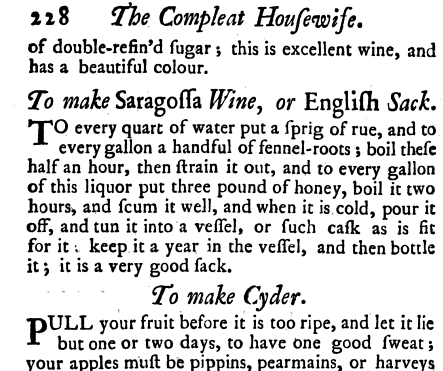

Sometimes it’s spelled differently within the same book. In Eliza Smith’s 1739 The Compleat Housewife, the index spells it “cider”, but it’s “cyder” in the text.

While not as many as in Middle English, one can still find “cider” spelled in various ways in more modern English. In the seventeenth through the early nineteenth centuries the common ways to spell cider had dwindled to cider, cidre, cyder, and sider. It’s only been within the last two hundred years that “cider” became the standard spelling for alcoholic apple juice. Those older words continue to be used today as some new cideries have adopted the old spellings.

Despite what anyone might suggest, the different spellings don’t represent different products or types of cider. They’re just the result of our weird and wonderful language.(1)

************************************

- In 1895 George Birdwood argued that since “cyder” was often historically spelled with a “y,” that is the correct spelling and that “cider” with an “i” was wrong. In his 1982 History and Virtue of Cyder, R.K. French used the different spellings to distinguish what he thought was a superior product from what he thought was an inferior one saying, “We are all familiar with pasteurized, diluted, bland, and carbon-dioxide-injected cider, but cyder is a living wine….”(p. 3) As the post above shows, these distinctions are an individual’s choice and not indicative of any real difference. You may noticed that on this blog I refer to the historically-inspired alcoholic apple juice I make at home as “cyder” and everything else as “cider.” It’s only because I like the historical association of “cyder” and not because I think it’s a truly separate thing.

For more on the history of English and its spelling, check out these resources:

History of English Podcast (this is a favorite and inspired this post)

On the history of the letter C see Episode 5: Centum, Satem and the Letter C

On the history of the Latin Alphabet see Episode 35: English Sounds and Roman Letters

On vowel sounds and their changes see Episode 88: The Long and Short of It

A Brief History of English Spelling

Spelling and Standardization in English: Historical Overview